東山文化を英語で説明・紹介するための基本情報と、英会話に役立つ表現をシンプルでわかりやすい英語で紹介します。

英会話ダイアローグ・関連情報・10の質問を通して、東山文化に関する英語表現を学びます。

記事の最後には、音声での深掘り解説もあります。リスニング力アップや、内容をさらに深く知りたい方におすすめです。

英語

英会話ダイアローグを読む前に知っておくと良い前提知識と情報は以下の通りです。

- 東山文化の概要

- 東山文化は室町時代後期(15世紀後半)に発展

- 将軍足利義政の時代に栄え、京都の東山地区が中心

- 「わび・さび」の美意識

- 「わび」は簡素で質素な美しさを意味し、「さび」は時の流れや古びた美しさを意味する

- 東山文化はこの美意識を重んじている

- 代表的な文化・芸術

- 重要な場所

- 重要な人物

- 足利義政: 東山文化を推進した将軍

- 村田珠光: 茶道の基礎を築いた人物

- 雪舟: 東山文化を代表する水墨画家

- 池坊専慶: 生け花の創始者とされる人物

2人が東山文化について話しています。

東山文化の特徴、代表的な場所や人物、「わび・さび」の美意識、茶道、水墨画、生け花などを話題にしています。

会話 / dialogue

Hey Key, I’ve been really interested in Higashiyama Culture lately. Do you know much about it?

Yes, I do! Higashiyama Culture developed during the late Muromachi period. It’s known for its simplicity and elegance, which influenced many aspects of Japanese culture.

That’s fascinating. Can you tell me more about its key features?

Sure. One of the main features is the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic, which values austere and serene beauty. This is reflected in the tea ceremony, ink wash painting, and ikebana.

I know a bit about the tea ceremony. How did it develop during this period?

The tea ceremony really flourished under the influence of Zen Buddhism. Murata Juko, an important figure, introduced the concepts of “wabi” and “sabi.” The ceremony emphasizes simplicity, spirituality, and harmony.

What about ink wash painting? Any famous artists?

Yes, Sesshu Toyo a renowned artist during this time. His works like “Autumn and Winter Landscapes” and “Long Scroll of Landscapes” are great examples of the period’s minimalist and profound style.

I also heard that ikebana became popular. Is that true?

Exactly. Ikebana, or flower arrangement, developed significantly during the Higashiyama period. It focuses on simplicity and natural beauty, influenced by Zen spirituality.

Are there any famous places I should visit to experience Higashiyama Culture?

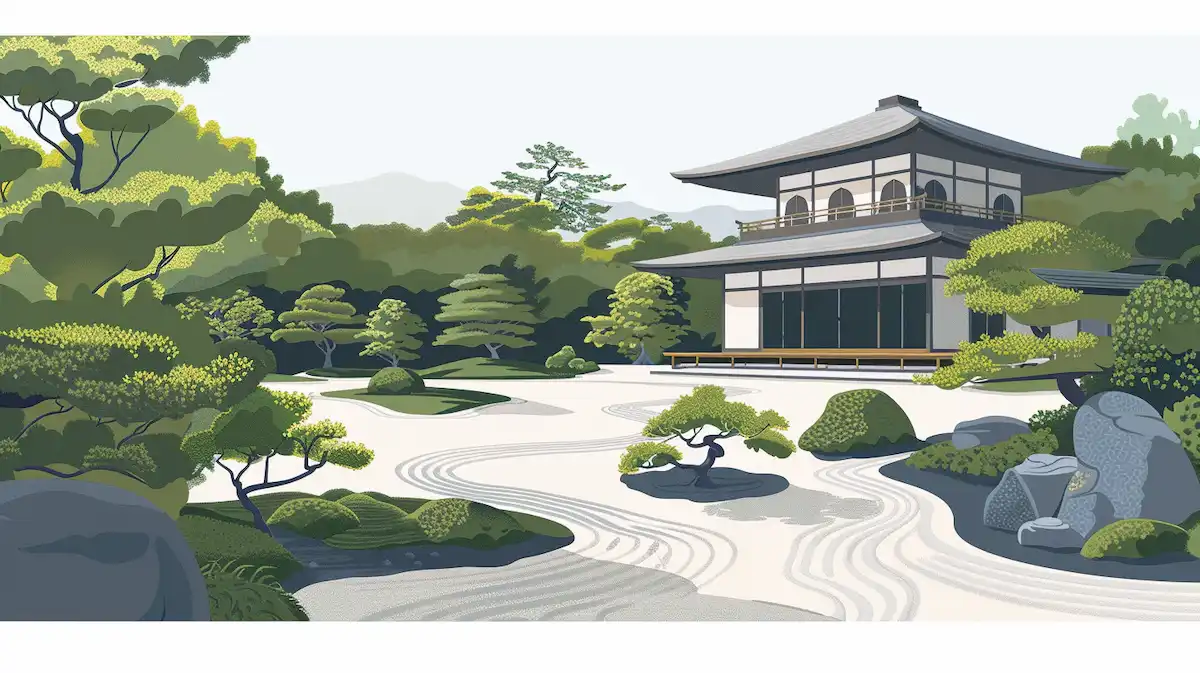

Definitely. Ginkaku-ji, also known as the Silver Pavilion, is a must-see. It’s a symbol of Higashiyama Culture. The rock garden at Ryoan-ji is another famous site that embodies the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic.

I’ve read about Ginkaku-ji. It’s Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s retirement villa, right?

Yes, that’s correct. It’s surrounded by beautiful gardens and reflects the simple yet elegant design typical of the period.

How did Higashiyama Culture influence later periods?

It had a significant impact on later Japanese culture, particularly during the Momoyama and Edo periods. The aesthetic principles of simplicity and elegance continued to influence various art forms and practices.

This is all so interesting. I want to explore more about Higashiyama Culture. Do you have any suggestions on where I can learn more?

You can visit museums that focus on Japanese history and art, read books on the subject, or even take part in tea ceremonies and ikebana classes to get a hands-on experience.

Great idea! I’ll start with visiting Ginkaku-ji and Ryoan-ji. Thanks for all the information, Key.

You’re welcome, Mack. Enjoy your exploration of Higashiyama Culture!

関連情報 / related information

「東山文化」について、理解を深めるための「英語での関連情報」です。

東山文化

Overview of Higashiyama Culture

Higashiyama Culture developed in the late Muromachi period, especially under the rule of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It is known for its focus on simplicity and elegance. This culture had a big impact on Japanese art, architecture, and lifestyle.

Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic

The concept of “wabi-sabi” is central to Higashiyama Culture. “Wabi” means simple, humble beauty, while “sabi” means the beauty of aging and the passage of time. This aesthetic values quiet, understated beauty and imperfection.

Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony, or “chanoyu,” became very important during this time. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, it emphasizes simplicity, spirituality, and harmony. Murata Juko, a key figure, helped develop the tea ceremony’s basic principles.

Ink Wash Painting

Ink wash painting, or “sumi-e,” also flourished. Famous artist Sesshu created beautiful monochrome paintings that reflect the minimalist and profound style of the period. These paintings use black ink to create different shades and effects.

Ikebana

Ikebana, the art of flower arrangement, developed significantly. It focuses on simple and elegant arrangements that reflect nature’s beauty. Ikenobo Senkei is considered the founder of Ikebana during this period.

Important Places

Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion) is a famous site from this period. It was the retirement villa of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and symbolizes Higashiyama Culture. The rock garden at Ryoan-ji is another important place, known for its simple and serene beauty.

10の質問 / 10 questions

「東山文化」について、理解を深めるための「英語での10の質問」です。

1: What is Higashiyama Culture?

Higashiyama Culture developed during the late Muromachi period. It emphasizes simplicity, elegance, and the appreciation of beauty through art, tea ceremonies, and Zen Buddhism.

2: When did Higashiyama Culture begin?

Higashiyama Culture began in the late 15th century, during the rule of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who greatly influenced its development.

3: What are the main features of Higashiyama Culture?

The main features are simplicity, the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic, and an emphasis on spiritual beauty found in art forms like tea ceremonies, ink wash painting, and ikebana.

4: What is the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic?

"Wabi-sabi" is the appreciation of beauty in imperfection, simplicity, and the passage of time. It is a key concept in Higashiyama Culture.

5: What is Ginkaku-ji?

Ginkaku-ji, or the Silver Pavilion, is a Zen temple in Kyoto built by Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It is a symbol of Higashiyama Culture, known for its simple and elegant design.

6: How did Zen Buddhism influence Higashiyama Culture?

Zen Buddhism influenced Higashiyama Culture by promoting simplicity, mindfulness, and the importance of spiritual practice, especially in the tea ceremony and garden design.

7: Who is Sesshu Toyo?

Sesshu Toyo was a famous Japanese ink wash painter during the Higashiyama period. He is known for his minimalist and expressive landscapes.

8: What is ikebana?

Ikebana is the traditional Japanese art of flower arrangement. It became popular during the Higashiyama period, focusing on simplicity and natural beauty.

9: How did the tea ceremony develop in Higashiyama Culture?

The tea ceremony flourished during Higashiyama Culture, emphasizing simplicity, spirituality, and harmony, influenced by Zen Buddhism and promoted by figures like Murata Juko.

10: What is the significance of Ryoan-ji's rock garden?

Ryoan-ji's rock garden is a famous example of Zen garden design. It embodies the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic and is admired for its simplicity and serene beauty.

和訳付

会話 / dialogue

Hey Key, I’ve been really interested in Higashiyama Culture lately. Do you know much about it?

ねえキー、最近東山文化にすごく興味があるんだ。よく知ってる?

Yes, I do! Higashiyama Culture developed during the late Muromachi period. It’s known for its simplicity and elegance, which influenced many aspects of Japanese culture.

そうなんだ!東山文化は室町時代後期に発展したよ。簡素さと優雅さで知られていて、日本文化の多くの側面に影響を与えたんだ。

That’s fascinating. Can you tell me more about its key features?

それは興味深いね。もっと特徴について教えてくれる?

Sure. One of the main features is the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic, which values austere and serene beauty. This is reflected in the tea ceremony, ink wash painting, and ikebana.

もちろん。「わび・さび」の美意識が主要な特徴の一つで、質素で静かな美しさを重視しているんだ。これは茶道や水墨画、生け花に反映されているよ。

I know a bit about the tea ceremony. How did it develop during this period?

茶道について少し知ってるよ。この時期にどう発展したの?

The tea ceremony really flourished under the influence of Zen Buddhism. Murata Juko, an important figure, introduced the concepts of “wabi” and “sabi.” The ceremony emphasizes simplicity, spirituality, and harmony.

茶道は禅宗の影響を受けて本当に発展したんだ。重要な人物である村田珠光が「わび」と「さび」の概念を導入したんだ。茶道は簡素さ、精神性、調和を重視しているよ。

What about ink wash painting? Any famous artists?

水墨画についてはどう?有名な画家はいるの?

Yes, Sesshu Toyo was a renowned artist during this time. His works like “Autumn and Winter Landscapes” and “Long Scroll of Landscapes” are great examples of the period’s minimalist and profound style.

うん、雪舟等楊はこの時期の有名な画家だよ。「秋冬山水図」や「四季山水図巻」などの作品は、この時代のミニマリズムで深いスタイルの素晴らしい例なんだ。

I also heard that ikebana became popular. Is that true?

生け花も人気があったって聞いたけど、それは本当?

Exactly. Ikebana, or flower arrangement, developed significantly during the Higashiyama period. It focuses on simplicity and natural beauty, influenced by Zen spirituality.

その通り。生け花は東山時代に大きく発展したんだ。シンプルさと自然の美しさに焦点を当てていて、禅の精神の影響を受けているんだ。

Are there any famous places I should visit to experience Higashiyama Culture?

東山文化を体験するために訪れるべき有名な場所はある?

Definitely. Ginkaku-ji, also known as the Silver Pavilion, is a must-see. It’s a symbol of Higashiyama Culture. The rock garden at Ryoan-ji is another famous site that embodies the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic.

もちろん。銀閣寺(銀閣)という名でも知られている場所は必見だよ。東山文化の象徴なんだ。竜安寺の石庭も「わび・さび」の美意識を体現する有名な場所だよ。

I’ve read about Ginkaku-ji. It’s Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s retirement villa, right?

銀閣寺について読んだことがあるよ。足利義政の隠居所だよね?

Yes, that’s correct. It’s surrounded by beautiful gardens and reflects the simple yet elegant design typical of the period.

そう、正解。美しい庭園に囲まれていて、時代特有のシンプルで優雅なデザインを反映しているんだ。

How did Higashiyama Culture influence later periods?

東山文化は後の時代にどう影響したの?

It had a significant impact on later Japanese culture, particularly during the Momoyama and Edo periods. The aesthetic principles of simplicity and elegance continued to influence various art forms and practices.

桃山時代や江戸時代を中心に、後の日本文化に大きな影響を与えたんだ。簡素さと優雅さの美的原則は、さまざまな芸術形式や実践に影響を与え続けたよ。

This is all so interesting. I want to explore more about Higashiyama Culture. Do you have any suggestions on where I can learn more?

全部とても興味深いよ。もっと東山文化について探求したいな。どこで学べるか何か提案はある?

You can visit museums that focus on Japanese history and art, read books on the subject, or even take part in tea ceremonies and ikebana classes to get a hands-on experience.

日本の歴史や芸術に焦点を当てた博物館を訪れたり、関連する本を読んだり、茶道や生け花のクラスに参加して実際に体験するのもいいよ。

Great idea! I’ll start with visiting Ginkaku-ji and Ryoan-ji. Thanks for all the information, Key.

いいアイデアだね!まずは銀閣寺と竜安寺を訪れてみるよ。ありがとう、キー。

You’re welcome, Mack. Enjoy your exploration of Higashiyama Culture!

どういたしまして、マック。東山文化の探求を楽しんでね!

関連情報 / related information

東山文化

Overview of Higashiyama Culture

Higashiyama Culture developed in the late Muromachi period, especially under the rule of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It is known for its focus on simplicity and elegance. This culture had a big impact on Japanese art, architecture, and lifestyle.

東山文化の概要

東山文化は室町時代後期、特に将軍足利義政の治世下で発展しました。簡素さと優雅さに焦点を当てたことで知られています。この文化は日本の芸術、建築、ライフスタイルに大きな影響を与えました。

Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic

The concept of “wabi-sabi” is central to Higashiyama Culture. “Wabi” means simple, humble beauty, while “sabi” means the beauty of aging and the passage of time. This aesthetic values quiet, understated beauty and imperfection.

わび・さびの美意識

「わび・さび」の概念は東山文化の中心です。「わび」はシンプルで謙虚な美しさ、「さび」は古びた美しさや時間の経過を意味します。この美意識は静かで控えめな美しさと不完全さを重視します。

Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony, or “chanoyu,” became very important during this time. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, it emphasizes simplicity, spirituality, and harmony. Murata Juko, a key figure, helped develop the tea ceremony’s basic principles.

茶道

茶道、または「茶の湯」はこの時期に非常に重要になりました。禅宗の影響を受け、簡素さ、精神性、調和を重視しています。重要な人物である村田珠光が茶道の基本原則を発展させました。

Ink Wash Painting

Ink wash painting, or “sumi-e,” also flourished. Famous artist Sesshu created beautiful monochrome paintings that reflect the minimalist and profound style of the period. These paintings use black ink to create different shades and effects.

水墨画

水墨画、または「すみえ」も発展しました。有名な画家である雪舟は、この時代のミニマリズムで深いスタイルを反映した美しいモノクロ絵画を制作しました。これらの絵画は、黒インクを使ってさまざまな陰影や効果を生み出します。

Ikebana

Ikebana, the art of flower arrangement, developed significantly. It focuses on simple and elegant arrangements that reflect nature’s beauty. Ikenobo Senkei is considered the founder of Ikebana during this period.

生け花

生け花、または花の生け方の芸術も大いに発展しました。自然の美しさを反映したシンプルで優雅な配置に焦点を当てています。この時期に池坊専慶が生け花の創始者とされています。

Important Places

Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion) is a famous site from this period. It was the retirement villa of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and symbolizes Higashiyama Culture. The rock garden at Ryoan-ji is another important place, known for its simple and serene beauty.

重要な場所

銀閣寺(銀閣)はこの時期の有名な場所です。足利義政の隠居所であり、東山文化の象徴です。竜安寺の石庭もまた重要な場所で、その簡素で静かな美しさで知られています。

10の質問 / 10 questions

1: What is Higashiyama Culture?

東山文化とは何ですか?

Higashiyama Culture developed during the late Muromachi period. It emphasizes simplicity, elegance, and the appreciation of beauty through art, tea ceremonies, and Zen Buddhism.

東山文化は室町時代後期に発展しました。簡素さと優雅さを強調し、芸術や茶道、禅宗を通じて美を鑑賞します。

2: When did Higashiyama Culture begin?

東山文化はいつ始まりましたか?

Higashiyama Culture began in the late 15th century, during the rule of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who greatly influenced its development.

東山文化は15世紀後半に始まり、将軍足利義政の治世下で大きく発展しました。

3: What are the main features of Higashiyama Culture?

東山文化の主な特徴は何ですか?

The main features are simplicity, the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic, and an emphasis on spiritual beauty found in art forms like tea ceremonies, ink wash painting, and ikebana.

主な特徴は簡素さ、「わび・さび」の美意識、そして茶道、水墨画、生け花などに見られる精神的な美しさの強調です。

4: What is the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic?

「わび・さび」の美意識とは何ですか?

"Wabi-sabi" is the appreciation of beauty in imperfection, simplicity, and the passage of time. It is a key concept in Higashiyama Culture.

「わび・さび」は不完全さ、簡素さ、そして時間の経過における美を鑑賞することです。東山文化の重要な概念です。

5: What is Ginkaku-ji?

銀閣寺とは何ですか?

Ginkaku-ji, or the Silver Pavilion, is a Zen temple in Kyoto built by Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It is a symbol of Higashiyama Culture, known for its simple and elegant design.

銀閣寺(銀閣)は、足利義政によって建てられた京都の禅寺です。東山文化の象徴で、シンプルで優雅なデザインで知られています。

6: How did Zen Buddhism influence Higashiyama Culture?

禅宗はどのように東山文化に影響を与えましたか?

Zen Buddhism influenced Higashiyama Culture by promoting simplicity, mindfulness, and the importance of spiritual practice, especially in the tea ceremony and garden design.

禅宗は簡素さや心の静けさ、精神的修行の重要性を強調することで、特に茶道や庭園設計において東山文化に影響を与えました。

7: Who is Sesshu Toyo?

雪舟等楊とは誰ですか?

Sesshu Toyo was a famous Japanese ink wash painter during the Higashiyama period. He is known for his minimalist and expressive landscapes.

雪舟等楊は東山時代の有名な日本の水墨画家です。彼はミニマリズムで表現豊かな風景画で知られています。

8: What is ikebana?

生け花とは何ですか?

Ikebana is the traditional Japanese art of flower arrangement. It became popular during the Higashiyama period, focusing on simplicity and natural beauty.

生け花は日本の伝統的な花の生け方の芸術です。東山時代に人気を博し、簡素さと自然の美しさに焦点を当てました。

9: How did the tea ceremony develop in Higashiyama Culture?

茶道は東山文化でどのように発展しましたか?

The tea ceremony flourished during Higashiyama Culture, emphasizing simplicity, spirituality, and harmony, influenced by Zen Buddhism and promoted by figures like Murata Juko.

茶道は東山文化の時期に発展し、簡素さ、精神性、調和を強調しました。禅宗の影響を受け、村田珠光のような人物によって推進されました。

10: What is the significance of Ryoan-ji's rock garden?

竜安寺の石庭の重要性は何ですか?

Ryoan-ji's rock garden is a famous example of Zen garden design. It embodies the "wabi-sabi" aesthetic and is admired for its simplicity and serene beauty.

竜安寺の石庭は禅庭園設計の有名な例です。「わび・さび」の美意識を体現し、その簡素さと静かな美しさで称賛されています。

words & phrases

英会話ダイアローグと関連情報に出てきた単語・フレーズです(例文は各3つ)。

simplicity: 名詞

意味: 単純さ、簡素さ。The quality of being easy to understand or not complicated.

(東山文化では、簡素さと優雅さが重要な美的価値として重視される)

例文

The simplicity of the tea ceremony reflects Zen principles.

「茶道の簡素さは禅の原則を反映しています。」

She admired the simplicity of the traditional Japanese house.

「彼女は伝統的な日本家屋の簡素さに感心しました。」

Simplicity in design can lead to timeless elegance.

「デザインの簡素さは時を超えた優雅さにつながることがあります。」

aesthetic: 形容詞

意味: 美の、美学の。Concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty.

(東山文化の美意識、「わび・さび」の美学を指す)

例文

The aesthetic qualities of the garden are truly unique.

「その庭の美的品質は本当に独特です。」

She has a strong aesthetic sense in her artwork.

「彼女の作品には強い美的感覚があります。」

The aesthetic appeal of the architecture attracted many visitors.

「その建築の美的な魅力が多くの訪問者を引き付けました。」

austere: 形容詞

意味: 厳しい、簡素な。Severe or strict in manner, attitude, or appearance; simple or plain.

(東山文化では、質素で飾り気のない美しさを意味する)

例文

The monk lived an austere life in the temple.

「その僧侶は寺院で厳しい生活を送っていました。」

The austere design of the room reflects simplicity.

「部屋の厳しいデザインは簡素さを反映しています。」

Her austere demeanor made her seem unapproachable.

「彼女の厳しい態度は近寄りがたい印象を与えました。」

serene: 形容詞

意味: 静かな、穏やかな。Calm, peaceful, and untroubled.

(東山文化の静かで落ち着いた美しさを意味する)

例文

The garden is a serene place for meditation.

「その庭は瞑想に最適な静かな場所です。」

She felt serene after a long walk by the lake.

「湖のそばを長く散歩した後、彼女は穏やかな気持ちになりました。」

The serene expression on his face showed his inner peace.

「彼の顔の穏やかな表情は内なる平和を示していました。」

embody: 動詞

意味: 具体化する、体現する。To give a tangible or visible form to an idea, quality, or feeling.

(東山文化の価値観や美学を具体的に表現することを指す)

例文

The temple’s design embodies the principles of simplicity.

「その寺院のデザインは簡素さの原則を具体化しています。」

Her artwork embodies the essence of traditional Japanese culture.

「彼女の作品は伝統的な日本文化の本質を体現しています。」

The leader embodies the values of the community.

「その指導者はコミュニティの価値観を具体化しています。」

詳細情報 / Further Info

関連記事(銀閣寺)

音声解説 / In-depth Audio Discussion

ここからは、今回の記事内容をさらに深く掘り下げる英語音声対談です。

理解を深めたい方やリスニング力を伸ばしたい方におすすめです。

音声を聞きながら、英語と日本語の両方の表現も一緒に学べます。

※ダイアローグのテキストと和訳も以下に掲載していますので、音声と合わせてご利用ください。

英語音声対談

テキスト(英語)

A: All right, let’s uh delve into something truly captivating today. Picture this time in Japan. The thing shifted, you know, from grand and opulent towards something.

B: Yeah.

A: Quieter, deeper, really profoundly beautiful. We’re about to sort of unpack the secrets of Higashiyama culture. A really pivotal period that, well, it utterly reshaped Japanese art and philosophy.

B: Exactly. And our guide for this journey, it’s a foundational text on Higashiyama culture. It’s um really rich with insights, clear explanations. Our goal today is basically to distill the essence of it, the most important bits so you, the listener, can get a clear grasp of its core ideas and uh its lasting influence.

A: Okay, great. So to start off, where exactly did this transformation, this uh Higashiyama culture, where did it take root and when did it really become prominent?

B: Right. So Higashiyama culture emerged uh during the late Muromachi period. We’re talking specifically the latter half of the 15th century and its heartland geographically was the Higashiyama district in Kyoto. A lot of it revolved around the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. He was, you know, the big military leader then. And his personal taste, his patronage, I mean, his financial backing was huge. It didn’t just support the culture. It really shaped its principles, pushed for this new kind of refined simplicity, elegance that really defined the era.

A: That’s fascinating. A powerful ruler basically steering things towards simplicity. Interesting. But at the core of it all, there’s this concept we hear a lot, wabi-sabi. It sounds so profound, but what does it actually mean? You know, beyond just the dictionary definition.

B: Yeah, this is where it gets really insightful. Wabi-sabi isn’t just an aesthetic. It’s well, it’s almost a challenge to how we usually think about beauty. Wabi speaks to the beauty of humility, like quietude, a sort of rustic simplicity. Finding contentment in something unadorned. Think of maybe a simple handmade table. Maybe it’s a little uneven, but it feels right. It serves its purpose perfectly. That’s kind of wabi. Sabi, then, is different. It embraces the beauty that comes with age, with impermanence, the quiet passage of time, the natural flaws that emerge. Imagine like an old wooden bench worn smooth where people have sat, darkened by touch over decades. It gains this unique character, right? Something brand new and polished just doesn’t have that deep quiet beauty from age and genuine use. That’s the heart of sabi. So together, wabi-sabi invites us to find beauty not in perfection or flashiness, but in what’s authentic, imperfect, natural, ephemeral. It’s a real shift in perspective.

A: Wow. Okay. So, it’s not just simplicity, but things that actively show time passing, that embrace their story, flaws included. That feels like quite a leap from, you know, our modern obsession with the brand new, the flawless. So, how did such a profound, almost counterintuitive idea translate into, well, real things? How did wabi-sabi show up in the art forms back then?

B: Oh, it permeated almost everything. Take the tea ceremony, cha. It went through a massive transformation around this time. It evolved from something quite formal, aristocratic, into a practice that was deeply spiritual. Zen Buddhism was a huge influence, emphasizing simplicity, quiet, reverence, harmony. There’s this key figure, Murata Juko. He’s really credited with infusing wabi and sabi right into the tea practice itself. Consciously moving away from the showy, expensive tea wares that were popular before.

A: Right. Simplifying the whole ritual.

B: Exactly. And this focus on understated beauty, it wasn’t just tea. It profoundly influenced visual arts too, like ink wash painting, sumi-e. This art form really blossomed. You had masters like Sesshu Toyo creating these incredibly minimalist yet spiritually deep landscapes. His works, um, things like autumn and winter landscapes or his long scroll of landscapes, they’re amazing. Just using black ink, he could suggest immense depth, different shades, vastness, all with just a few brush strokes. It really embodies that idea of finding profound beauty in stark simplicity, very Zen, focusing on the essence.

A: I think, incredible.

B: Yeah. And then this reverence for nature combined with Zen, it also found expression in ikebana, the art of flower arrangement. It developed significantly during the Higashiyama period too. The focus shifted toward simplicity, natural elegance. So instead of big elaborate bouquets, ikebana aimed to highlight the inherent beauty of maybe just one stem, a few leaves, a single flower, often with symbolic meaning tied in, again reflecting that spiritual depth and appreciating nature’s unadorned forms. A figure named Senkei is seen as uh foundational here, establishing many ikebana principles during this time.

A: That’s amazing how these deep philosophical ideas were just woven into everyday practices, into art. So, if we wanted to really feel this today, to experience the Higashiyama aesthetic, where would we go in Japan? Are there places where these ideas are still really visible?

B: Absolutely. Yeah. Two places definitely spring to mind as kind of epitomes of Higashiyama culture. First, you really have to consider Ginkakuji. It’s often called the Silver Pavilion or Jishoji. This was actually Yoshimasa’s retirement villa. And it remains this powerful, tangible symbol of the era. Its design is striking. It’s simple, unpainted wood, very elegant. A real contrast to the more famous Golden Pavilion, which is much more ornate, and the gardens around it, the moss garden, the dry sand garden—they’re masterpieces of contemplative design, really beautiful examples of wabi-sabi.

A: Okay, Ginkakuji, got it.

B: And then there’s Ryoanji’s rock garden. This might be one of the most famous Zen gardens anywhere and it perfectly, absolutely perfectly captures that wabi-sabi feeling. It’s a classic example of karesansui, a dry landscape garden. You get this incredible serene beauty from just, well, 15 stones arranged minimalist style in raked white sand. The whole space is designed for quiet contemplation. It really invites you to find meaning in that quiet, unassuming setup.

A: Just stones and sand, yet so famous. It’s clear this period left a huge mark on its own time. But what about later? How did this unique culture influence later Japanese history, later art? What’s the lasting ripple effect?

B: Oh, that’s a crucial point. The influence was profound, really far-reaching. Higashiyama culture deeply impacted subsequent Japanese culture, especially during the periods that followed like Momoyama and Edo. Its core aesthetic principles, that love for simplicity, elegance, the beauty in imperfection—they didn’t just vanish. They became foundational. They kept shaping art forms, architecture, garden design, countless cultural practices for centuries. They really helped form the broader Japanese identity we kind of recognize today. It set a whole new standard for what was beautiful and meaningful.

A: What an illuminating deep dive. Seriously, we’ve journeyed through this unique mix of simplicity, elegance, and that deep spiritual core that defines Higashiyama culture. This has definitely felt like a shortcut to understanding a really profound and beautiful part of Japanese history.

B: My pleasure. And you know, to really let this sink in, I’d suggest going beyond just reading about it. Try to seek out experiences that embody these principles. Maybe visit a museum with Japanese ceramics or ink paintings, or explore a local garden, but look differently this time. Look for simplicity, how age has softened things. Maybe deliberate imperfection in the design. Or honestly, just think about how that quiet beauty of the imperfect, the subtle signs of time passing, how you might find that in your own everyday surroundings.

A: That’s a wonderful thought to end on. How might truly seeing that quiet, understated beauty actually shift your perspective on the world around you? Something to ponder.

テキスト(和訳付)

A: All right, let’s uh delve into something truly captivating today. Picture this time in Japan. The thing shifted, you know, from grand and opulent towards something.

A: じゃあ、今日は本当に面白いテーマを深掘りしてみよう。日本のある時代を想像してみて。物事が豪華で華やかだったのが、ある方向へと変化したんだ。

B: Yeah.

B: うん。

A: Quieter, deeper, really profoundly beautiful. We’re about to sort of unpack the secrets of Higashiyama culture. A really pivotal period that, well, it utterly reshaped Japanese art and philosophy.

A: 静かで、深くて、本当に奥深い美しさ。その秘密、つまり東山文化をこれから紐解いていこうと思う。日本の芸術や思想を根本から変えた、とても重要な時代なんだ。

B: Exactly. And our guide for this journey, it’s a foundational text on Higashiyama culture. It’s um really rich with insights, clear explanations. Our goal today is basically to distill the essence of it, the most important bits so you, the listener, can get a clear grasp of its core ideas and uh its lasting influence.

B: まさにその通り。今回のガイドになるのは、東山文化に関する基本的な資料なんだ。洞察も説明も豊富だよ。今日はその本質や大事な部分をぎゅっとまとめて、聴いてくれている人が東山文化の核やその影響をしっかり理解できるようにしたい。

A: Okay, great. So to start off, where exactly did this transformation, this uh Higashiyama culture, where did it take root and when did it really become prominent?

A: いいね、じゃあまず聞きたいんだけど、この変化、つまり東山文化ってどこで生まれて、いつ本格的に広まったの?

B: Right. So Higashiyama culture emerged uh during the late Muromachi period. We’re talking specifically the latter half of the 15th century and its heartland geographically was the Higashiyama district in Kyoto. A lot of it revolved around the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. He was, you know, the big military leader then. And his personal taste, his patronage, I mean, his financial backing was huge. It didn’t just support the culture. It really shaped its principles, pushed for this new kind of refined simplicity, elegance that really defined the era.

B: そうだね。東山文化が生まれたのは室町時代の後期、特に15世紀後半なんだ。中心は京都の東山エリア。多くは将軍の足利義政を中心に展開された。彼が当時の有力な武士で、彼の美意識や支援、資金力がとても大きかった。ただ文化を支えただけじゃなくて、その根本的な考え方や、洗練されたシンプルさ、優雅さを時代の特徴にしたんだ。

A: That’s fascinating. A powerful ruler basically steering things towards simplicity. Interesting. But at the core of it all, there’s this concept we hear a lot, wabi-sabi. It sounds so profound, but what does it actually mean? You know, beyond just the dictionary definition.

A: それは面白いね。力のある権力者がシンプルさを目指したってことだよね。でもその中心には、「わび・さび」っていう言葉がよく出てくるけど、すごく深そうだよね。実際のところ、辞書の意味以上にどういうものなの?

B: Yeah, this is where it gets really insightful. Wabi-sabi isn’t just an aesthetic. It’s well, it’s almost a challenge to how we usually think about beauty. Wabi speaks to the beauty of humility, like quietude, a sort of rustic simplicity. Finding contentment in something unadorned. Think of maybe a simple handmade table. Maybe it’s a little uneven, but it feels right. It serves its purpose perfectly. That’s kind of wabi. Sabi, then, is different. It embraces the beauty that comes with age, with impermanence, the quiet passage of time, the natural flaws that emerge. Imagine like an old wooden bench worn smooth where people have sat, darkened by touch over decades. It gains this unique character, right? Something brand new and polished just doesn’t have that deep quiet beauty from age and genuine use. That’s the heart of sabi. So together, wabi-sabi invites us to find beauty not in perfection or flashiness, but in what’s authentic, imperfect, natural, ephemeral. It’s a real shift in perspective.

B: うん、ここが本当に面白いところだよ。「わび・さび」って、単なる美意識じゃなくて、普段の美しさの考え方に挑戦してるんだ。「わび」は、謙虚さとか静けさ、素朴なシンプルさの美しさ。飾り気のないものに満足を見出す感じ。例えば手作りのテーブルで、ちょっと歪んでいても、しっくりくるし、ちゃんと役割を果たしている。これが「わび」だね。「さび」はまた違って、年月を経ることで出てくる美しさや、移ろいや自然な変化、そこから生まれる味わい。たとえば長年使われて手触りが良くなった木のベンチとか、人が触れ続けて色が変わった部分とか。新品にはない、時を経たものだけが持つ深くて静かな美しさが「さび」なんだ。この2つが合わさることで、完璧さや派手さじゃなくて、本物で、不完全で、自然で、儚いものの中に美しさを見つける――そんな風にものの見方が変わるんだ。

A: Wow. Okay. So, it’s not just simplicity, but things that actively show time passing, that embrace their story, flaws included. That feels like quite a leap from, you know, our modern obsession with the brand new, the flawless. So, how did such a profound, almost counterintuitive idea translate into, well, real things? How did wabi-sabi show up in the art forms back then?

A: すごいね。つまり、単なるシンプルさじゃなくて、時間の流れや物語、不完全さを含めて受け入れることなんだ。今の新品志向や完璧主義とはだいぶ違う発想だよね。じゃあ、そんな深くて一見逆説的な考え方が、実際の「もの」や「芸術」にはどう現れたの?

B: Oh, it permeated almost everything. Take the tea ceremony, cha. It went through a massive transformation around this time. It evolved from something quite formal, aristocratic, into a practice that was deeply spiritual. Zen Buddhism was a huge influence, emphasizing simplicity, quiet, reverence, harmony. There’s this key figure, Murata Juko. He’s really credited with infusing wabi and sabi right into the tea practice itself. Consciously moving away from the showy, expensive tea wares that were popular before.

B: もう、ほとんどあらゆるものに染み渡ったよ。例えばお茶、つまり茶道。この時代に大きな変化があって、それまでの格式張った貴族的なものから、もっと精神性を大切にするものへと進化した。禅の影響が強くて、シンプルさや静けさ、敬意や調和が重視されるようになった。村田珠光という人物が、お茶の世界にわび・さびを取り入れた第一人者と言われている。それまで流行っていた派手で高価な茶道具から、意識的に離れていったんだ。

A: Right. Simplifying the whole ritual.

A: なるほど。儀式そのものをシンプルにしたんだね。

B: Exactly. And this focus on understated beauty, it wasn’t just tea. It profoundly influenced visual arts too, like ink wash painting, sumi-e. This art form really blossomed. You had masters like Sesshu Toyo creating these incredibly minimalist yet spiritually deep landscapes. His works, um, things like autumn and winter landscapes or his long scroll of landscapes, they’re amazing. Just using black ink, he could suggest immense depth, different shades, vastness, all with just a few brush strokes. It really embodies that idea of finding profound beauty in stark simplicity, very Zen, focusing on the essence.

B: そう。その控えめな美しさへのこだわりは、お茶だけじゃなくて、絵画、特に水墨画にも大きな影響を与えた。水墨画はこの時代に本当に花開いて、雪舟のような名人が、極限までシンプルなのに精神性の高い風景を描いた。秋や冬の景色や長い巻物など、黒い墨だけで奥行きや濃淡、広がりを表現できる。ほんの少しの筆づかいで、深い美しさや本質を追求する――まさに禅の精神そのものなんだ。

A: I think, incredible.

A: すごいよね、本当に。

B: Yeah. And then this reverence for nature combined with Zen, it also found expression in ikebana, the art of flower arrangement. It developed significantly during the Higashiyama period too. The focus shifted toward simplicity, natural elegance. So instead of big elaborate bouquets, ikebana aimed to highlight the inherent beauty of maybe just one stem, a few leaves, a single flower, often with symbolic meaning tied in, again reflecting that spiritual depth and appreciating nature’s unadorned forms. A figure named Senkei is seen as uh foundational here, establishing many ikebana principles during this time.

B: そうだね。それから、自然への敬意と禅の精神が合わさって生まれたのが生け花。これも東山時代に大きく発展したんだ。豪華な花束ではなくて、一本の枝や一輪の花、数枚の葉など、自然のままの美しさを引き立てる方向にシフトした。そこには象徴的な意味が込められていたりして、精神的な深さや自然の姿を大事にしたんだ。専慶という人物が、この時期に多くの生け花の基本を作ったとされているよ。

A: That’s amazing how these deep philosophical ideas were just woven into everyday practices, into art. So, if we wanted to really feel this today, to experience the Higashiyama aesthetic, where would we go in Japan? Are there places where these ideas are still really visible?

A: そういう深い哲学が、日常の行いや芸術の中に自然に取り入れられてるってすごいね。じゃあ今、その東山文化の美意識を体感したいとき、日本のどこに行けば見られるんだろう?今でも残っている場所ってあるのかな?

B: Absolutely. Yeah. Two places definitely spring to mind as kind of epitomes of Higashiyama culture. First, you really have to consider Ginkakuji. It’s often called the Silver Pavilion or Jishoji. This was actually Yoshimasa’s retirement villa. And it remains this powerful, tangible symbol of the era. Its design is striking. It’s simple, unpainted wood, very elegant. A real contrast to the more famous Golden Pavilion, which is much more ornate, and the gardens around it, the moss garden, the dry sand garden—they’re masterpieces of contemplative design, really beautiful examples of wabi-sabi.

B: もちろんあるよ。東山文化を象徴する場所として思い浮かぶのが2つあって、まず銀閣寺(慈照寺)は外せない。ここは実は義政の隠居所だったんだ。今でも時代の象徴として残っていて、無垢の木でシンプルだけどとても上品なデザインが特徴だよ。有名な金閣寺とは対照的で、周囲の苔庭や白砂の庭も瞑想的で、「わび・さび」の美しさを感じられる場所なんだ。

A: Okay, Ginkakuji, got it.

A: なるほど、銀閣寺ね。

B: And then there’s Ryoanji’s rock garden. This might be one of the most famous Zen gardens anywhere and it perfectly, absolutely perfectly captures that wabi-sabi feeling. It’s a classic example of karesansui, a dry landscape garden. You get this incredible serene beauty from just, well, 15 stones arranged minimalist style in raked white sand. The whole space is designed for quiet contemplation. It really invites you to find meaning in that quiet, unassuming setup.

B: それから龍安寺の石庭も有名だね。ここは世界でも指折りの禅庭で、「わび・さび」の感覚を完璧に体現している場所だよ。まさに枯山水の代表例で、白砂の上に15個の石がシンプルに配置されている。その静かな美しさは圧倒的で、全体が静かに自分と向き合うために作られていて、地味だけど奥深い意味を感じられるんだ。

A: Just stones and sand, yet so famous. It’s clear this period left a huge mark on its own time. But what about later? How did this unique culture influence later Japanese history, later art? What’s the lasting ripple effect?

A: 石と砂だけなのに、そんなに有名なんだね。この時代が当時に与えた影響は大きかったと思うけど、その後の日本の歴史や芸術にも影響を与えたの?どんな波及効果があったのかな。

B: Oh, that’s a crucial point. The influence was profound, really far-reaching. Higashiyama culture deeply impacted subsequent Japanese culture, especially during the periods that followed like Momoyama and Edo. Its core aesthetic principles, that love for simplicity, elegance, the beauty in imperfection—they didn’t just vanish. They became foundational. They kept shaping art forms, architecture, garden design, countless cultural practices for centuries. They really helped form the broader Japanese identity we kind of recognize today. It set a whole new standard for what was beautiful and meaningful.

B: そこがすごく大事なポイントだよ。東山文化の影響は本当に大きくて、桃山時代や江戸時代にも深く残ったんだ。シンプルさや優雅さ、不完全さの美しさといった美意識は消えることなく、日本文化の土台となった。何世紀にもわたって芸術や建築、庭園デザイン、さまざまな文化活動に影響を与え続けて、日本人のアイデンティティの形成にも大きく関わったんだ。何が美しくて価値があるのかという基準を、まったく新しいものに変えたとも言えるよ。

A: What an illuminating deep dive. Seriously, we’ve journeyed through this unique mix of simplicity, elegance, and that deep spiritual core that defines Higashiyama culture. This has definitely felt like a shortcut to understanding a really profound and beautiful part of Japanese history.

A: すごく勉強になったよ。本当に、シンプルさや優雅さ、そして深い精神性――まさに東山文化の核となる部分を一緒に巡ってきたね。日本史の中でもこんなに奥深くて美しい部分を、近道で理解できた気がするよ。

B: My pleasure. And you know, to really let this sink in, I’d suggest going beyond just reading about it. Try to seek out experiences that embody these principles. Maybe visit a museum with Japanese ceramics or ink paintings, or explore a local garden, but look differently this time. Look for simplicity, how age has softened things. Maybe deliberate imperfection in the design. Or honestly, just think about how that quiet beauty of the imperfect, the subtle signs of time passing, how you might find that in your own everyday surroundings.

B: どういたしまして。せっかくなら本を読むだけじゃなくて、実際にこうした美意識を体験してみるといいよ。たとえば日本の陶芸や水墨画がある美術館に行ってみたり、近くの庭園を歩いてみたり。でも今度は「シンプルさ」とか、時間がたって柔らかくなった雰囲気、意図的な不完全さを意識してみて。あるいは普段の生活でも、不完全さや時の流れがもたらす静かな美しさを探してみると、世界の見え方が変わるかもしれない。

A: That’s a wonderful thought to end on. How might truly seeing that quiet, understated beauty actually shift your perspective on the world around you? Something to ponder.

A: 素敵な締めくくりだね。静かで控えめな美しさを本当に見つけることで、自分の周りの世界の見え方がどう変わるんだろう。ちょっと考えてみたいな。